Last updated on March 20th, 2018 at 02:22 pm

The nearly-indestructible honey badger, famed for its ability to endure venomous snakebites, is Bitcoin’s animal mascot for a good reason. Over the years, Bitcoin has survived so many technical attacks, so much internal strife, and so much outside criticism that it’s gained a reputation for antifragility. This term, coined by economist Nassim Taleb, is used to describe something that thrives in adverse conditions:

“Some things benefit from shocks; they thrive and grow when exposed to volatility, randomness, disorder, and stressors and love adventure, risk, and uncertainty…Antifragility is beyond resilience or robustness. The resilient resists shocks and stays the same; the antifragile gets better.”

– Nassim Nicholas Taleb

From this perspective, perhaps the surest way to kill Bitcoin would be to stop challenging it. However, in a world of fiercely competing currencies—fiat, altcoins, and precious metals—such destructive tranquility seems unlikely. For the foreseeable future, anticipate further attacks and “Bitcoin is dead!” declarations.

Attacks on Bitcoin: Past, Present, and Future

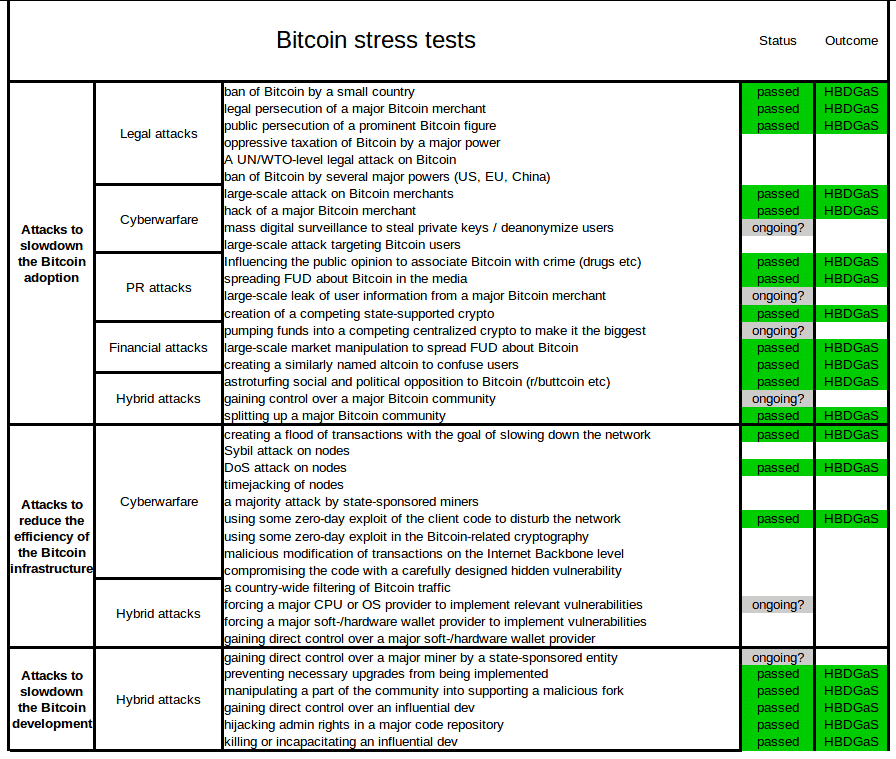

A few months ago, Reddit user themetalfriend compiled a fairly comprehensive list of attacks on Bitcoin. In case you’re wondering about the “Outcome” column, “HBDGaS” stands for “Honey Badger Don’t Give a S#!%,” referencing a viral video about the animal’s survivability.

While different categories or additional attacks could be proposed, the list effectively conveys the wide variety of attacks that Bitcoin has endured—as well as some potential future threats.

There are three broad categories of attack, with significant feedback between them:

- Attacks to slow Bitcoin adoption are primarily targeted at users and the user experience. Cryptocurrencies live or die by their network effects; their utility—and hence, their value—is predicted by the square of their users. By slowing Bitcoin adoption, rivals from both inside and outside the crypto sphere can advance their own currencies.

- Attacks to degrade Bitcoin infrastructure target network nodes, miners, and their underlying hardware or software. By slowing or disrupting the network and driving up fees, rivals worsen the Bitcoin user experience, which damages the economy and slows adoption. Such attacks also divert developer resources from improvement.

- Attacks to slow Bitcoin development target Bitcoin developers directly or target their development process. This has the effect of slowing upgrades, which in turn slows adoption. Such attacks may also damage developers’ ability to respond to infrastructure attacks.

As you can see, even though there are three different categories, in the end, they’re all connected in their outcomes. Let’s consider these specific attacks in greater detail, including known examples and their counters.

8 Ways to Killing Bitcoin by Slowing Down Its Adoption

Legal Attacks

When authorities pass and enforce legislation against Bitcoin, the ultimate effect is the punishment of users. The list correctly notes that Bitcoin has survived several outright bans by small countries (namely Afghanistan, Algeria, Bangladesh, Bolivia, Ecuador, Morocco, Macedonia, Vanuatu, and Vietnam). In fact, such bans have gone largely unnoticed outside of these places.

However, any prohibition by large, systemically important countries or major powers (the United States, the European Union, China) has yet to occur. The closest example of a ban by a major nation would be Russia, where Bitcoin’s legal status appears to be in a constant state of flux.

Numerous false reports of bans by large countries, notably China and South Korea, have been known to cause price drops, sometimes significantly. However, a low “bargain” price may spur adoption in other countries, so compensatory forces likely exist across the market. Low prices may hurt holders, but it’s possible they spur adoption too. It should also be remembered that even at a suppressed price, Bitcoin still works.

Can Bitcoin be Banned?

While nations may discourage the use of Bitcoin by prosecuting known users, any ban on citizen interaction with the network would be technically unenforceable. Blockstream satellites currently broadcast the blockchain to the Americas, Africa, and Western Europe and will soon cover the entire globe, so a fairly inexpensive satellite setup can still receive blockchain data even if it’s scrubbed from a nation’s internet (as part of a country-wide filtering of Bitcoin traffic).

As for sending transactions to the blockchain, multiple stealthy methods exist: over Tor, via SMS, within an encrypted email or other text message, or even using steganography to encode transactions within seemingly-innocuous digital files.

According to Andreas Antonopoulos, this image of cute kittens hides a 550,000 BTC transaction.

Thus, banning Bitcoin would be a losing game of whack-a-mole for authorities. Code can be (re)written a lot faster than legislation, so authorities will always lag development. Even an internationally-coordinated UN/WTO-level legal attack would likely only have the effect of forcing Bitcoin underground, incentivizing the development of privacy features, and perhaps raising its value as a contraband item (as occurred with narcotics).

As for the persecution of Bitcoin merchants or figures, this has certainly occurred. Examples include the incarceration of Ross Ulbricht, accused of being the mastermind behind the Silk Road darknet marketplace, and Charlie Shrem, charged with acting as an unlicensed money transmitter. As darknet markets and decentralized exchanges have proliferated and evolved since such harsh examples were made of Ulbricht and Shrem, it appears that such legal risks fail to discourage user involvement, instead encouraging increasing technical sophistication.

Cyberwarfare

Cyberwarfare is hacking and social media manipulation conducted by state-level actors. We’ll take it to mean general hacking by any person, group, or agency. Bitcoin itself has so far proven resilient to hackers despite the massive multibillion-dollar reward it represents. Bitcoin is a hard target mostly due to its decentralized nature and proof-of-work system.

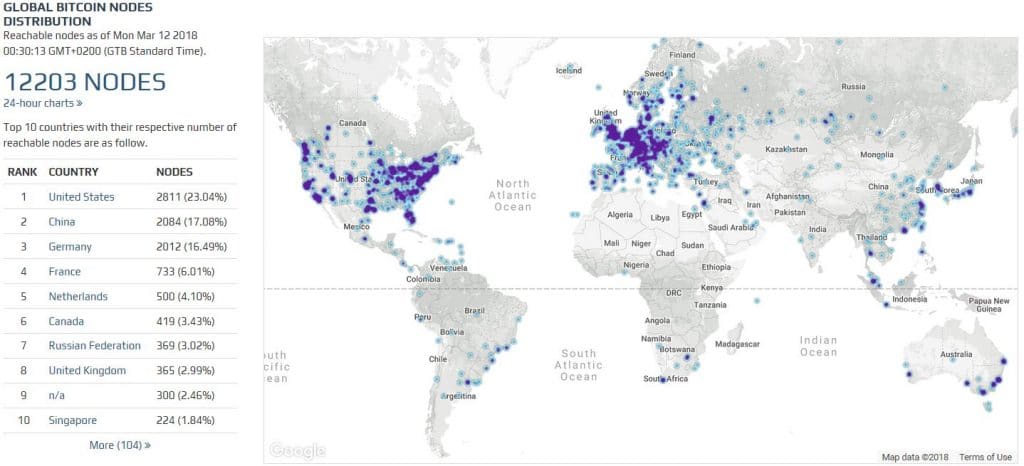

If hackers alter their version of Bitcoin’s code to attempt such exploits, transactions that break the established rules are immediately rejected by the network at large. The more independent full nodes in the network, the less likely such an attack is to work (currently there are over 12,000 that we know of).

If hackers attempt to rewrite the blockchain in their favor, they can only succeed by controlling more hash rate than all honest miners. Even then, the proof-of-work algorithm may be changed in response, neutralizing the massive hardware investment required to pull it off.

Unfortunately, Bitcoin users and services are far more vulnerable to hacking…

Cyber Attacks Slowing Adoption

Numerous hacks of major Bitcoin merchants (particularly exchanges, such as Mt. Gox and Bitfinex) have occurred over the years. Over 1 million BTC have been stolen in this way. Such hacks certainly slow adoption; users who lose funds may be unwilling to buy back into Bitcoin.

Mainstream media frequently amplifies the PR damage of such hacks, spreading FUD about Bitcoin in the media by failing to draw a clear distinction between the hacking of a crypto-related company and a “Bitcoin hack.” This certainly increases skepticism regarding Bitcoin’s safety among the non-technical public.

State-Mandated Privacy Attacks

Mass digital surveillance to steal private keys/deanonymize users is advanced and ongoing due to the anti-money laundering and know your customer regulations imposed on all clients of fiat exchanges and, in some cases, services. It’s hard to say whether ID verification requirements have had a chilling effect on adoption, as anonymous trading methods still exist.

However, by sharing their details, users are placed at greater risk. If a merchant’s site is compromised, client data is exposed to identity thieves in a large-scale leak of user information from a major Bitcoin merchant. This could, in turn, easily lead to a potential large-scale attack (online or offline) targeting Bitcoin users. Furthermore, tax agencies may demand client information from merchants (as recently happened with Coinbase), exposing users to all kinds of unexpected payment demands.

PR Attacks

Influencing public opinion to associate Bitcoin with crime is so common. Both the mainstream press and politicians play this card frequently. A 2017 study revealed that more people believed that Bitcoin was being used for illegal rather than legal purchases, although the reverse is likely true by a large margin.

Any thinking person soon realizes that fiat currencies are involved in far more—and worse—crimes. Research suggests that most darknet purchases were of soft drugs, such as cannabis and ecstasy. A recent Europol reported no confirmed evidence of Bitcoin terror financing.

Financial Attacks

The creation of a competing state-supported crypto occurred with the advent of Venezuela’s Petro, although the “competing” part is arguable. The Petro has so far failed to gain traction and had minor real-world economic impact. Should a more powerful country bring out an official crypto and support it financially and with propaganda, the results could be quite different. Such a state-controlled crypto would likely be fully centralized and not really comparable to Bitcoin, although it could nevertheless absorb some of Bitcoin’s market share.

Stealing Bitcoin’s thunder

As for creating a similarly-named altcoin to confuse users also known as a Bitcoin fork (or forkcoin), the prime example of this is Bitcoin Cash, aka Bcash. The Bcash attack is the most persistent and well-financed attack so far. It includes the following elements:

- Pumping funds into a competing centralized (Bcash is mined almost entirely by Bitmain) crypto to make it the biggest — See the failed Operation Dragonslayer.

- Large-scale market manipulation to spread FUD about Bitcoin — See the high volume of anti-Bitcoin articles on r/btc.

- Astroturfing social and political opposition to Bitcoin — See above. A common claim is that Bcash is the “real Bitcoin” despite its forking off from Bitcoin because it meets some twisted interpretation of Satoshi’s white paper. Also common is the reference to Bitcoin as “Bitcoin Core.”

- Splitting up a major Bitcoin community — r/btc split off from r/bitcoin, citing “censorship” when prevented from promoting various fork attempts.

- Gaining control over a major Bitcoin “community” — Unfortunately, Bcash advocates control the #Bitcoin Twitter account as well as the Bitcoin.com domain. These official-seeming outlets are used to spread Bcash misinformation, amplifying newcomer confusion.

While some new users have certainly been deceived by this “evil doppelganger” attack, it’s probable that Bitcoin’s relative technical and economic merits will soon become so obvious (with the introduction of the Lightning Network) that no more newcomers will be deceived.

2 Attacks for Degrading Bitcoin’s Infrastructure

Cyber Attacks on the Network

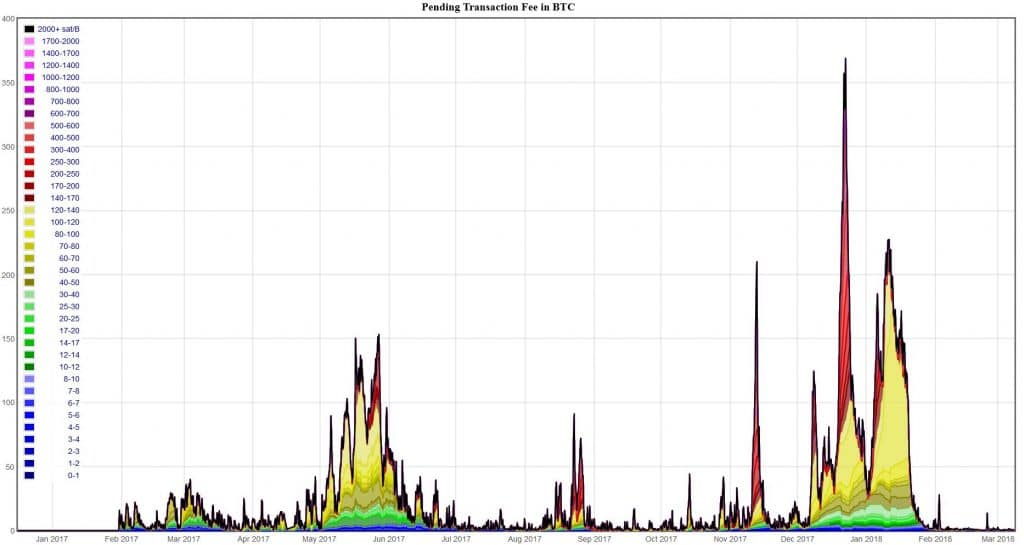

Creating a flood of transactions with the goal of slowing down the network (aka spam attacks) also serves to raise Bitcoin transaction fees. Such attacks have been carried out multiple times. Those with the most to gain from such attacks are altcoin and forkcoin proponents, who point to the resultant congestion on Bitcoin’s blockchain as a reason to use their cryptocurrencies. By spamming the Bitcoin network, direct competitors such as Bcash manufacture a plausible reason for their own existence. Such spam attacks are often combined with PR attacks across traditional, alternative, and social media.

Spam attacks are easily spotted when transaction fees spike.

If timed to coincide with periods of high demand, such as major price movements, spam attacks are capable of causing a great deal of disruption and discontent. The cost and difficulty of such attacks are raised via the improvement of Bitcoin’s scalability as achieved by SegWit and, soon, the Lightning Network. The better Bitcoin scales, the more costly such attacks become—with one exception…

If miners conspire to perform the spam attack, they can largely recover their own spam transaction fees while raising transaction fees for all users, thus boosting their mining income through higher fees. However, much like the well-known 51% attack, this act runs counter to a miner’s economic incentives. A sluggish, high-fee network is likely to at least restrain Bitcoin’s price appreciation as users resort to cheap, fast altcoins for value transmission. Thus, whatever extra profit miners rake in from elevated fees will be offset by lower Bitcoin prices.

Similar economic incentives discourage many other possible attacks by miners. However, many fear a majority attack by state-sponsored miners, specifically due to the centralization of Bitcoin mining and ASIC hardware manufacturing in China and by Bitmain.

As the US dollar’s reign as the global reserve currency appears to be ending, some speculate that Bitcoin may (partially) replace it in this capacity. Such developments could motivate the Chinese government to force its miners to act toward political objectives and against miners’ economic interests. However, the fact that the People’s Bank of China is reducing energy supply to miners and thus forcing their geographic dispersal is evidence against against any such plan.

Sybil/timejacking/DoS (denial of service) attacks on nodes can all cause disruption and are known weaknesses. These attacks demand a lot of computing resources but can be mitigated or even neutralized: most Bitcoin clients will automatically ban misbehaving nodes. With the current Bitcoin node count over 12,000, it would take an extremely well-financed and sophisticated adversary to cause any severe impact on the network.

High-Level Cyber Attacks

Bitcoin’s zero-day exploit (an attack that exploits a previously unknown security vulnerability) refers to the Value Overflow Incident, in which 184 billion bitcoins were erroneously created in August 2010. The bug was patched within five hours, and the blockchain forked to erase the transactions. The incident was minor only because it occurred at a time when very few people were using Bitcoin. If such a thing were to happen today, it’d cause considerable chaos, major losses, and dreadful PR.

An exploit in Bitcoin-related cryptography, such as a break of SHA-256 (used for proof-of-work mining) or the secp256k1 ECDSA curve (used for public/private keys), would be catastrophic and would require an immediate change of the affected part. It’s likely that numerous other applications besides Bitcoin would be impacted by such a breach. Certain security experts predict that quantum computing may be capable of breaking Bitcoin’s crypto within ten years. Should this possibility become imminent, Bitcoin will likely switch to quantum-resistant algorithms.

The further network attacks listed in the Cyberwarfare and Hybrid Attacks section are, according to the Snowden revelations, well within the capabilities of major signals intelligence agencies, such as the NSA or GCHQ, at least. In terms of forcing a major CPU or OS provider to implement relevant vulnerabilities, it’s known that all major Silicon Valley tech firms—Microsoft, Apple, Google, Facebook, and the like—have been cooperating with intelligence agencies for ages.

The recently-uncovered Meltdown and Spectre vulnerabilities in modern CPUs could be used to reveal Bitcoin private keys even on hardened systems running open-source operating systems. While a hardware wallet might protect against such an outcome, there’s also the possibility of an agency gaining direct control over a major software/hardware wallet provider or intercepting hardware wallets in transit to compromise them.

Compromising the code with a carefully-designed hidden vulnerability is another tactic such agencies have been known to use. Concerns regarding this possibility were heightened when former Bitcoin Core developer Gavin Andresen visited the CIA in 2011. Given the number of eyes (and the knowledge behind them) inspecting Bitcoin’s code, such a vulnerability would have to be exceptionally brilliant to sneak past.

In summation: It’s likely that, given the scope of their known operations, a well-funded agency could cause significant damage to Bitcoin. However, as by doing so they could reveal capabilities and methods they’d rather keep hidden, intel agencies are unlikely to mount serious attacks on Bitcoin without strong political motivation.

How to Slow Down Bitcoin’s Development

Preventing necessary upgrades from being implemented is best exemplified by the attack infamously conducted by Bitmain. Bitmain attempted to block the SegWit soft fork, which threatened its ability to use the covert AsicBoost mining exploit. Ultimately, despite numerous ploys, Bitmain’s wealth and near-monopoly on mining was overcome by the greater network.

r/btc frequently attacks Bitcoin developers, often targeting Greg Maxwell or Luke Dashjr in particular, but such attacks have been largely confined to social media spats and Bitcoin.com’s reporting thereof.

While the loss of major contributors would certainly hamper development efforts, at worst it would cause Bitcoin’s development to stagnate at its current functional level. Potentially more damaging would be gaining direct control over an influential developer if said developer was able to send development down a dead end. This appeared to be the motivation behind Gavin Andresen and Jeff Garzik’s push for bigger blocks as a scaling solution.

Is Bitcoin Indestructible?

While it seems that Bitcoin keeps coming back from the dead, let’s not get too cocky. Anything can be destroyed—even Bitcoin. Fortunately, the way Bitcoin was built, the trials it has already endured, and the current macroeconomic state of the world make it very robust and hard to eliminate.

The real stress test will probably come during the next financial crisis. Until then, I’ll leave you with this Green Beret’s take on how he would take down Bitcoin.

https://99bitcoins.com/how-to-kill-bitcoin/

BTC-USD

BTC-USD  ETH-USD

ETH-USD  LTC-USD

LTC-USD  XRP-USD

XRP-USD